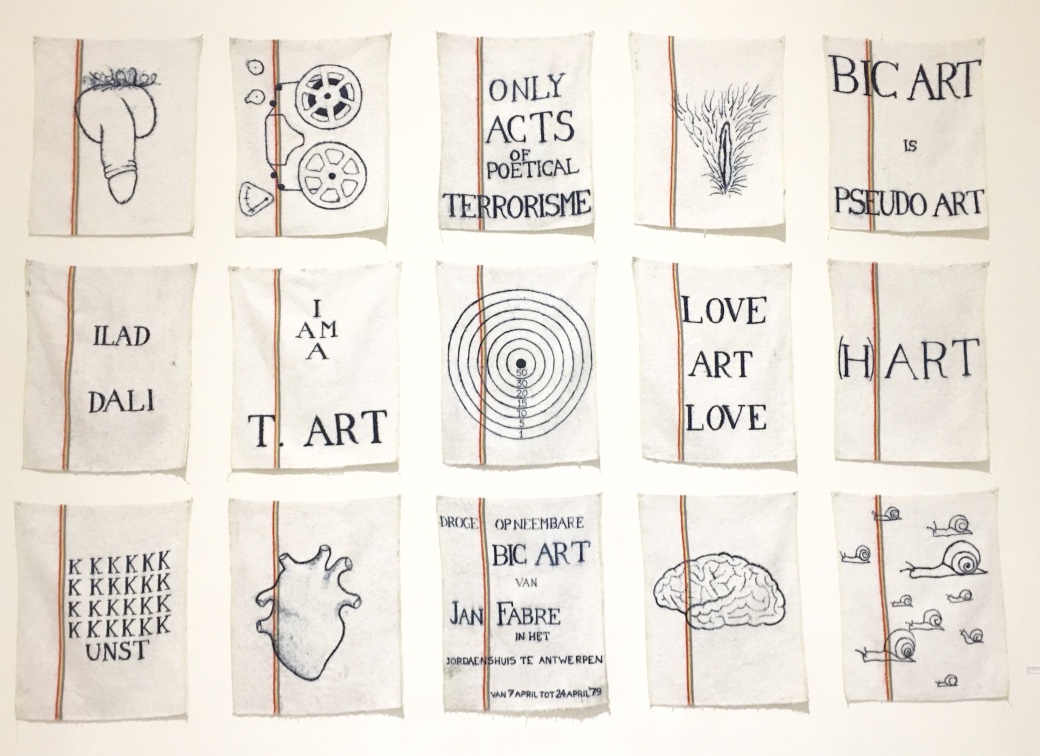

On exhibit was the riotously funny and mentally challenging oeuvre of Belgian artist Jean Fabre. Acknowledged as one of the late 20th century’s most successful contemporary artists, Fabre also seems also to have at least a few seriously loose screws. Who in their right mind, for example, would use various weights of sandpaper to scrape the paint off the legs of a wooden table and then do the same to his own shaven legs until they bled, making paintings with the dripping blood? I must give Fabre credit for both creatively balanced composition and for exchanging flesh and blood for canvass and palette. Sanding table legs bare then sanding your own legs raw, now that is some bad ass parallel construction, and very hard to blot out of your mind once you’ve seen it.

Most of Jean Fabre’s work has been captured on film with remarkable quality and editing and noteworthy performances. He has certainly mastered the art of making an absurd premise believable. One noteworthy performance was a collaboration with avant garde filmmaker Pierre Coulibeuf called ‘Doctor Fabre Will Cure You’ (2013). Standing pope-like on a balcony, dressed in a white doctor’s jacket and surrounded by the cut up parts of hogs, Fabre addresses a crowd. “Dr. Fabre will cure you!” he proclaims, picking up the face of a slaughtered pig and working the hinged jaw open and closed. “Use your mouth!” he shouts, tossing the pig face to the crowd. He picks up two eyeballs, holds them to his own eyes then throws them to the crowd. “Use your eyes!” Alas, he plucks two ears from the balcony handrail and holds them to the sides of his head. “Use your ears!” he calls and throws them to the crowd. “Dr. Fabre will cure you!”

Much of Fabre’s work resonates with the idea that we have forgotten our animal nature, a completely valid artistic message, especially if it puts us in touch with other species. A hilarious skit places him in the bowels of a subway dressed in knight’s armor flailing a sword over his head with both hands. Between the heft of the sword and the bulk of the armor he is continually staggering and falling down and flailing to get back to his feet. It is an extremely Quixotic scene as the only enemy Fabre is battling in the tunnel is his own inability to remain standing. A beautiful woman appears and tells him, “Remember, you are an animal.” Maybe this is beginning to make sense.

John and our mother watched an entire movie of Fabre’s antics while I further explored the grounds of the museum which included a number of commercial kilns. Maybe the monks were ceramicists? I’m not sure if Dr. Fabre cured us but throughout our visit we talked about his sanded legs and his dancing on a marble staircase like Fred Astaire while cats were randomly tossed in the air in the foreground. Another film showed him shot numerous times in a vest followed by his beautiful girlfriend, convincingly pretending she was a dog, sniffing over his slumped bloody body. There’s only one person in the world who can make this stuff up.

We went from the museum to a Flamenco show in Seville’s Triana District and experienced an entirely different form of performance art. It was highly emotional and transcendent and spontaneous. A guitarist came on stage by himself and played a solo composition that blended Spanish classical and Flamenco. He brandished his instrument with astonishing virtuosity. Then a male and female dancer and a male and female singer and percussionist joined him on the stage and the show gathered intensity as they took turns performing in various configurations. There was clapping and toe and heel tapping on the wooden board in the center of the stage and the rhythmic response of the guitarist to the dancer’s feet and the singers’ clapping in a display of practiced improvisation, the right hand of the guitarist responding precisely to the rhythms tapped and kicked by the dancers. There was the exquisite singing of a long haired well dressed man who could hold a note quavering with mournful semitones for at least two minutes. With barely a movement he breathed and began anew with the beautiful dancer spinning and diving and furiously tapping and convincingly telling a story so timeless and other worldly. David Byrne wrote that “we hear with our eyes,” meaning that we experience live performances on a variety of sensory levels of which the most important may be sight. Truer words may have never been spoken.

The dictionary sheds this light on the etymology of performance.

perform (v.)

c. 1300, “carry into effect, fulfill, discharge,” via Anglo-French performer, altered (by influence of Old French forme “form”) from Old French parfornir “to do, carry out, finish, accomplish,” from par- “completely” (see per-) + fornir “to provide” (see furnish).

Theatrical/musical sense is from c. 1600. The verb was used with wider senses in Middle English than now, including “to make, construct; produce, bring about;” also “come true” (of dreams), and to performen muche time was “to live long.” Related: Performed; performing.

On a simplistic level, the way we live our lives truly becomes our art and in that respect, each step along the way contributes to the performance. But in the end, as in art, we know authenticity when we see it.