It was the morning of my tenth birthday. My dad and I had tickets to see the Phillies host the Astros at Connie Mack Stadium. But outside it was pouring, a typical late August thunderstorm in south-central Pennsylvania. I’d been waiting for this game all summer and it was hard to hold back my disappointment. Being the soft hearted and generous soul he was, my father agreed to make the three-hour roundtrip to Philadelphia regardless of the storm.

We arrived at the ancient ballpark in time for the first pitch, the sun now blasting through the clouds. Except for a few thousand other hard core fans, we had the stadium to ourselves. Connie Mack was originally known as Shibe Park and opened in 1909 as the home of the Philadelphia Athletics. It had a nostalgic vibe with wooden seats and bleachers and ornamental wrought iron posts, the kind of place that came of age when Rogers Hornsby and Babe Ruth and Ty Cobb were stars. Connie Mack Stadium reached its glory (and highest single day turnout) when Jackie Robinson made his debut in a double header between the Phillies and the Brooklyn Dodgers on May 11, 1947.

The Phillies won that rainy August Sunday and I can say with over 50 years of experience that being a Phillies fan is like having malaria. It stays in your blood for life and at some point every summer you get sick.

Playing baseball was a big part of my identity growing up. Despite severe hay fever I loved the baseball season. Waiting for the pre-season to begin, the chance to play two games a week, the uniform, the crack of wooden and aluminum bats, the snack shop with snow cones and bubble gum and extra treats when we won. I even loved baseball as a catcher wearing all that extra gear in 98 degree weather with 100 percent humidity. To feed my passion I invented my own fantasy league long before anything like that ever existed, using a baseball card game and dice and meticulous score keeping.

The fields were in an industrial area of town. The grass was mowed regularly and the foul lines and batter’s box laid down with fresh lime before every game. There were dugouts made of cinder blocks and painted plywood advertisements on the outfield fences and an electronic scoreboard and an announcer. It was all serious business, which didn’t thrill my dad. He thought we kids should just be thrown in a pit with balls, bats and gloves and encouraged to make up our own rules. Sometimes my grandparents would come to watch. My Dad’s dad, Howard, had white hair and a white goatee and the kids would say, “Hey look, Colonel Sanders is here!” That was my grandpa.

For many years I was a very good player for my age and I think that had to do with my eyesight. When I was ten I hit a double off of Bob Fox who was two years older than me and really intimidating. I ripped a fastball off one of the wooden advertising plaques in center field. I must have been gloating because the next time I came up Bob Fox drilled me in the ribs, which left a bruise for about a week. Still, that double was worth it and foreshadowed the hitter I would become.

I remained an All Star for a number of years. My eyesight changed drastically between my twelfth and thirteenth years. I’ve worn prescription glasses ever since. That made catching harder and curtailed my peripheral vision.

The summer after eighth grade my parents agreed to send me to Mickey Owens Baseball Camp in Miller, Missouri. This was a huge deal. It meant flying on my own to St. Louis and venturing out in the world for the first time away from my family. I met kids from all over the country, including Carl from San Diego who had also just completed eighth grade. He had blond hair and talked like a surfer and his favorite expression was “Alrighty then!” Carl regaled me with stories about nickel bags of marijuana and one of his friends who had gotten his girlfriend pregnant in junior high school. That was a real eye opener. They grew up much faster on the West Coast.

The counselors were athletes who were trying to become pros. They timed our speed between home plate and first base with a stop watch. We had sessions on hitting, fielding, pitching and catching, the ins and outs of sliding. It was all baseball all the time. We played three games per day until the oppressive midwestern sun went down. I was still catching and wearing all that gear but I would soon transition to the outfield. I think it was around this time I began to realize that I might not have what it takes to be a professional baseball player. For a very select few baseball is a field of dreams. For others it’s where childhood dreams die.

I had promised my dad I would try out for the high school football team in return for sponsoring the trip to Missouri. I did try out but got injured very quickly. It wasn’t easy to start football in high school without having played formally at a younger age. I played baseball until my junior year. When I didn’t cut my hair high enough above my collar, I was cut from the team by coach Bushy. He was determined to weed out the Freaks from the Jocks. Somewhere along the line I had lost my competitive drive. Almost immediately I started playing guitar and studying ceramics and experimenting with drugs and alcohol and living closer to the life my San Diego friend Carl had described years earlier in the cabin at baseball camp.

To this day I spend way too much time following the malaria stricken Phillies. For many people it’s way too slow and much more of a game than a sport. I marvel at its innate brilliance, the hundred-mile per hour fastballs, the probability (and improbability) of a catcher throwing out someone trying to steal second base, the home runs and sacrifices and double plays, and just how hard it is to close out a game with a small lead. The one thing I can’t understand is the spitting. Why do they have to spit so much?

I’m offended when I hear someone say that so and so “sucks” when talking about a professional ball player. It’s so difficult to play baseball at the highest level, even though some days watching the pros feels like you’re at a Little League game. To be in that rarified company of people who make their living at a kid’s game is such an extraordinary accomplishment.

I am thinking in particular about a current Phillies player named Mark Appel. He was a high school star from California who went to Stanford and was selected number 1 in the Major League Draft by the Houston Astros. Then he went through a decade of setbacks — mental anxieties, injuries and illnesses. For years he carried the burden of being “the biggest Number 1 draft bust in the history of baseball.” He even stepped away from the game for a time.

Finally, this season, at the age of 30, Mark Appel walked onto the field at Citizen’s Bank in a Phillies uniform. It brought him to tears. In a recent article in the New York Times, after finally achieving his dream of playing on a major league field, Appel said:

“I came into this year knowing each day might be my last. Genuinely I was at a point where I was still trying to figure out what my role was — reliever, starter — do I still have it in me to put up good numbers, things like that. So if each day was going to be my last, I’m going to enjoy it. And I really enjoyed tonight.”*

These are words spoken from the deep well of the human spirit, which, more often than you may realize, finds its way onto a baseball field.

Now if we could only move beyond the spitting.

* “If Each Day Was Going to be My Last, I’m Going to Enjoy It,” New York Times, Victor Mather, June 30, 2022.

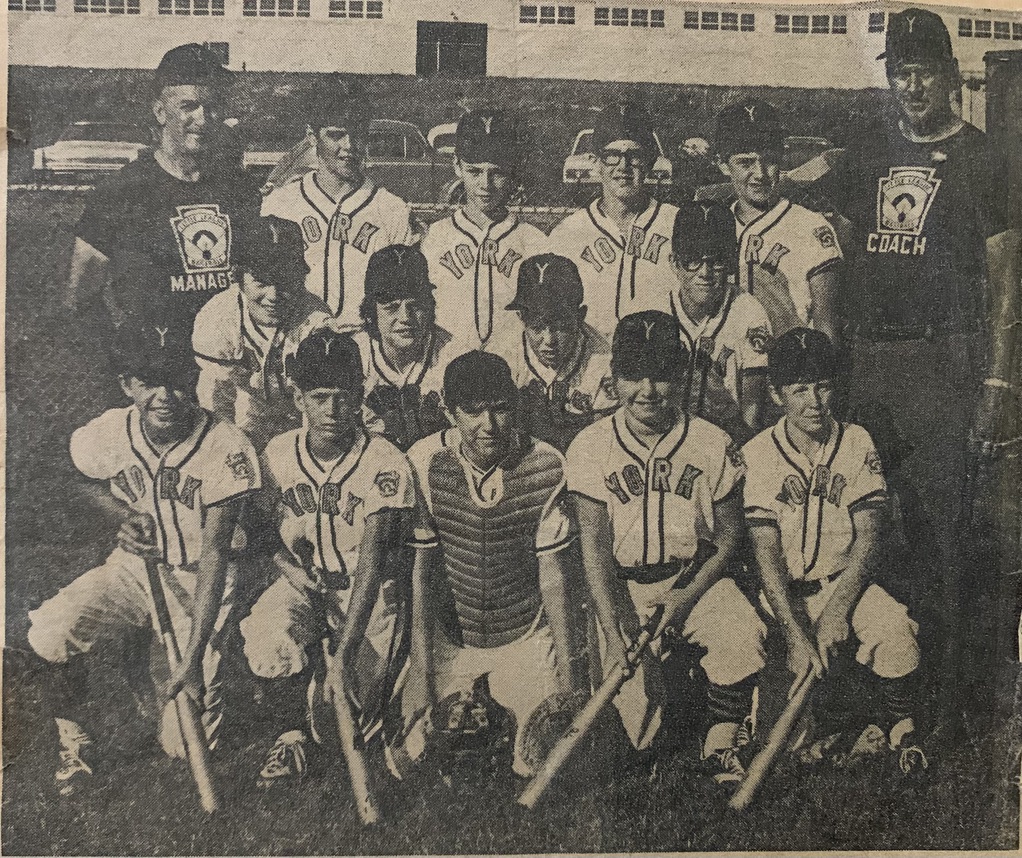

Photo: York Dispatch, Summer 1971, (middle row, second from left).

©2022, Dan Imhoff. All rights reserved.